Inspired by James Pawelski

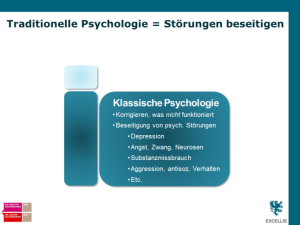

In 1998, Martin Seligman was elected president of the American Psychological Association (APA). Looking back on a fruitful career in research and teaching mostly on clinical psychology, especially the causes and treatment of depression, he had an epiphany that led to the formulation of a societal need for a positive psychology, a branch of psychology that would investigate a wide array of positive phenomena in human life, such as love, character strengths, high achievement, and in general: well-being and human flourishing. He proposed these issues should be investigated exerting the same scientific rigor that psychology has applied pertaining to negative phenomena (depression, anxiety, aggression etc.) for the first 100 years of its existence as an academic discipline. Equally, the rigorous scientific approach was meant to distinguish positive psychology from the extant self-help literature that partly expounds similar topics of interest (Seligman & Csíkszentmihályi, 2000; Seligman, 2002).

Academic disciplines that employ empirical approaches based on “hard” methods from the natural sciences (controlled experiments etc.) are oftentimes contrasted with “softer” approaches of (academic) inquiry such as the humanities (de Solla Price, 1986). Webster´s Third New International Dictionary (1971) defines humanities as “the branch of learning regarded as having primarily a cultural character and usually including languages, literature, history, mathematics, and philosophy”; and the Random House College Dictionary (1984) defines it as “a. the study of classical Latin and Greek language and literature. b. literature, philosophy, art, etc. as distinguished from the sciences.”

In spite of the aforementioned (conjectured) antagonism, the purpose of this essay is to shed light on the manifold interconnections between the humanities and positive psychology as a (comparatively) “hard” science. Specifically, the goal is to

- to show how insights from the humanities have informed (and still continue to inform) theories about the antecedents and characteristics of (psychological) well-being and what makes for a “good life”;

- how the humanities help to refine research on human flourishing in its different facets;

- how the humanities inform the practice of human flourishing and help to design interventions that are based on the insights of positive psychology.

1) How the Humanities inform Theories of Human Flourishing

For many centuries now, mankind has taken an interest in fostering its own psychological well-being and helping its fellow human being to lead a “good life”. Long before (positive) psychology, there has been an abundance of religious and spiritual leaders (such as the Buddha and Jesus Christ), philosophers (such as Aristotle and Marcus Aurelius), and writers/poets (such as Henry David Thoreau and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry) that have disseminated their concepts of ethics and morals, character and virtues, and what leads to joy and meaning in life (McMahon, 2012). For the sake of brevity, in this section I will only describe how writers and poets have sown the seeds for extant theories in positive psychology.

Telling stories is almost never done for sheer fun of it, or for objectively reporting on some occurrence. Telling stories, be it in traditional oral style, in print, or some audio-visual presentation mode, almost always has some instructive or prescriptive quality to it. Whoever creates or narrates the story typically wants to instill a change in the recipient, wants him to know or be something else when the story is over (Niles, 1999). This educational facet of storytelling can be traced through the literary history, from Homer´s “Iliad” and “Odyssey” and Aesop´s fables, to early religious accounts such as the “Upanishads” and the Bible, to medieval works such as Dante´s “Divine Comedy”, Shakespeare´s works of drama (e.g., “Hamlet”), to the early (e.g. Goethe´s “Wilhelm Meister´s Apprenticeship”) and later (e.g. Dickens´s “Great Expectations”) “Bildungsroman” – all the way up to 20th century masterpieces such as de Saint-Exupéry “Little Prince” and New Age classics along the lines of Bach´s “Jonathan Livingston Seagull” or Coelho´s “Alchemist”. Oftentimes, this educational element is conveyed by carefully depicting the protagonists´ lifestyles – in order to then confront the recipient with the outcomes of these modes of existence.

By way of example, both Leo Tolstoy´s “The Death of Ivan Ilych” (1886/2010) and Willa Cather´s “Neighbour Rosicky” (1932/2010) try to educate the reader (among other things) on the value of and human need for close relationships. While Cather portrays the distinctly positive outcomes of understanding that “no man is an island”, Tolstoy´s narrative describes Ivan Ilyich as a human being that literally dies of social and emotional isolation. So, while both stories do not contain any “how-to advice” such as modern self-help books, it remains unequivocal that they try to convey some underlying and implicit understanding of human well-being, that they represent a prescription for “a life well-lived”. As such, they can be likened to a kind of ideographic research, case-studies, a deep-dive into the personal experience of human beings as individuals (Jorgensen & Nafstad, 2004). Positive psychologists can draw on these sources to generate hypotheses about the general nature of human well-being (nomothetic research). They can take those extant descriptions and prescriptions, abstract and turn them into verifiable scientific hypotheses, and conduct large-scale and longitudinal empirical research to see if they turn out to be valid propositions.

By way of example, the sonnet „An sich“ by German 17th century poet Paul Fleming endorses a multitude of concepts and recommendations that are accepted as being beneficial to psychological well-being in positive psychology and (most self-help literature as well):

Sei dennoch unverzagt! Gib dennoch unverloren! Weich keinem Glücke nicht, steh höher als der Neid, vergnüge dich an dir und acht es für kein Leid, hat sich gleich wider dich Glück, Ort und Zeit verschworen.

Was dich betrübt und labt, halt alles für erkoren; nimm dein Verhängnis an. Laß alles unbereut. Tu, was getan muß sein, und eh man dir’s gebeut. Was du noch hoffen kannst, das wird noch stets geboren.

Was klagt, was lobt man noch? Sein Unglück und sein Glücke ist ihm ein jeder selbst. Schau alle Sachen an: dies alles ist in dir. Laß deinen eitlen Wahn, und eh du fürder gehst, so geh in dich zurücke. Wer sein selbst Meister ist und sich beherrschen kann, dem ist die weite Welt und alles untertan.

Among other things, Fleming advises his recipients to:

- retain an optimistic mindset in the face or hardships (Seligman & Schulman, 1986) and cultivate hopefulness (Snyder, 2002);

- exert self-control (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004) and tackle setbacks with a “gritty” attitude (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005);

- practice mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003) and “look inside” for sources of joy (Bryant, Smart, & King, 2005);

- express gratitude (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2006) and avoid feelings of envy and regret (Fredrickson, 2004).

All the aforementioned concepts can by now be considered “mainstream positive psychology”, as they are to a varying degree and scope building blocks of Seligman´s PERMA framework of human flourishing (2012). And while I am in some doubt whether the founding fathers of positive psychology have really been inspired by a German poet from the a 17th century, I am positively sure would they very much agree with what the latter had to say.

2) How the Humanities inform Research on Human Flourishing

As described in the introductory section, positive psychologists stress the importance of empirical research to back the claims made by this still rather new branch of psychology. While it might not be as apparent and straightforward as the insights from the first section of this paper, the humanities can also help to increase the quality of research in positive psychology. For instance, positive psychologists could draw on methods from philosophy to either improve existing methods within the field, or introduce largely new methods.

By way of example, methods from hilosophy can help positive psychology researchers to create better constructs and thus, questionnaires by engaging in conceptual clarification of central notions and frameworks in the field. Pawelski (2012) demonstrates how one of the core concepts in positive psychology, namely, the notion of “the positive” may still be severely underspecified. When the discipline was founded at the onset of the third millennium, it was not really clear what the term “positive” in positive psychology is actually referring to. 15 years later, science has made at least some progress pertaining to that question. Based on philosophical inquiry, Pawelski (2012) points out that the “positive” in positive psychology cannot just be the absence of something negative. Well-being cannot be explained by looking at what is not there (e.g., unhappiness, mental illness) – it has to look for something that is there in its own right.

In her essay, Tiberius (2012) tries to show how unique methods from philosophy can be introduced to the field of positive psychology to gain deeper insights into some topic of inquiry. For example, she demonstrates how the specific use of “intuition pumps” (short educational thought experiments) can shed valuable insight into functioning of human decision-making and moral reasoning. Schneider (2001) ultimately reminds positive psychologists not to be too sure of themselves when talking about the results of their research or judging the results of others. She insists that our perceptions and thus, knowledge, are necessarily characterized by a considerable degree of fuzziness – with all the benefits and disadvantages this entails. To that effect, philosophy can help positive psychology to stay humble – but also hungry for more knowledge.

3) How the Humanities inform the Practice of Human Flourishing

Man has been described – among many other analogies – as the “cultural animal” (Baumeister, 2005). Most people expose themselves to parts of our “cultural achievements” (music, books/writing, art, theater/films, spiritual rites etc.) on a daily basis. By way of example, listening to music is a pervasive element of most people´s lives.In a study using experiencing sampling, a method where subjects are to record what they do in their lives at certain intervals, it was found that music was present in 37% percent of the samples. Additionally, the researchers found that this exposure to music influenced the emotional state of the listeners in 67% of these events, and that this influence was oftentimes induced by the listeners on purpose, e.g., as a means to lift their mood (Juslin, Liljeström, Västfjäll, Barradas, & Silva, 2008). While other cultural practices are used for the same reasons (and several other “positive motives”) as well*, in light of this paper´s limited scope, I will concentrate on the question of how (and via which mechanisms) music may contribute to our psychological well-being.

Listening to music can lift our mood, has been shown to alleviate psychological stress as well as physical pain, and to contribute to our overall well-being (Västfjäll, Juslin, & Hartig, 2012). This may be a consequence of the uplifting effect of listening to music, but could also be a byproduct of its social aspect, since it is often performed and listened to in the presence of other human beings (MacDonald, Kreutz, & Mitchell, 2012). Additionally, making and listening to music is able to induce flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). For all these reasons, it is also used in a wide array of psychotherapeutic settings (Västfjäll, Juslin, & Hartig, 2012).

What is more, listening to music often leads us to moving our bodies/dancing, at least pre-consciously. In an article on the benefits of pursuing different forms of dancing as a hobby, Quiroga Murcia, Kreutz, Clift, and Bongard (2010) were able to demonstrate that dancing can:

- strengthen our immune system, thereby helping us to stay physically healthy;

- fight stress by decreasing the concentration of cortisol in our blood;

- improve our physical fitness, e.g., by fostering coordination, flexibility, and stamina;

- help us coping with pain;

- improve our self-esteem and build confidence.

In another study by Campion and Levita (2014), just five minutes of light dancing (alone) improved lateral thinking abilities of managers at work, and decreased their symptoms of fatigue.

In this sense, listening to music (and additionally, dancing) could very well be described as a positive intervention in its own right. It´s cheap, it´s available almost all over the planet, and – there are virtually no side effects. Of course, it´s important to keep in mind that different people display different tastes in music. Accordingly, Västfjäll, Juslin, and Hartig (2012) explain that the (beneficial) effect of music has to be understood as an interaction effect between the musical stimulus and its recipient: “Thus, there are no “pure” effects of music that will invariably occur regardless of the specific listener or situation. The response will depend on factors such as the listener´s music preferences and previous experiences, as well as on the specific circumstances of the context” (p. 408). Yet, assuming that most people are able and willing to choose what music they listen to at most times in their lives, it becomes clear that it is a potent ingredient of a life well-lived.

To close this section, I´d like to describe how I intend to use the extant knowledge on the connection of the humanities and well-being in my future professional life. I have been working as a management and life coach since 2008. Early on, I developed the habit of prescribing some homework to my clients in-between sessions. Once in a while, I would prescribe watching a film for inspiration, or seeding a certain idea (e.g., “The Kid” starring Bruce Willis, for the notion that it is possible to change our past; or rather, its emotional valence) by re-framing and re-evaluating certain experiences. To that effect, I also knew of the existence of “cinematherapy”, a rather recent branch of psychotherapy that utilizes the exposure to movies as a means to support the treatment of psychological disorders such as depression (Sharp, Smith, & Cole, 2002). All the more, I´ve been delighted to learn that positive psychology has also taken to this mode of delivery, namely in the form of Niemiec and Wedding´s (2008) tome “Positive psychology at the movies: Using films to build virtues and character strengths”. Over the upcoming months, I will read the book and watch as many films therein as possible to experience their impact – so as to build up my reservoir of movies to prescribe to my coaching clients. I am sure this will become a valuable addition to my “coaching toolbox”.

Conclusion

The objective of this essay was to demonstrate how insights from the humanities have influenced theories on the antecedents and characteristics of human flourishing, how the humanities help to refine research in this area, and how the humanities inform the practice of positive psychology and help to design beneficial positive interventions. I have pursued this objective by explaining how many of the core ideas in positive psychology can be traced back through our (literary) history, by showing how philosophy can improve research methods in that field as well as the “talk” about that research, and by illustrating how music can be used as an “active ingredient” in positive interventions.

Metaphorically speaking, positive psychology is still a very young tree, but it is a sapling with strong and far-reaching roots. These roots can be traced back in time looking into the realms of music, art, religion, philosophy, as well as oral, written, and audio-visual storytelling. In order to continue growing and ultimately becoming a strong and mighty tree, it´s of uttermost importance to get to know, acknowledge, and to treasure these roots. Mindfully exposing ourselves to the different manifestations of the humanities is such an approach to honor the roots of positive psychology.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (2005). The cultural animal: Human nature, meaning, and social life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822-848.

Bryant, F. B., Smart, C. M., & King, S. P. (2005). Using the past to enhance the present: Boosting happiness through positive reminiscence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 227-260.

Campion, M., & Levita, L. (2014). Enhancing positive affect and divergent thinking abilities: Play some music and dance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(2), 137-145.

Cather, W. (2010). “Neighbor Rosicky.” In Obscure destinies (pp. 1-38). Oxford, UK: Oxford City Press. (Original work published in 1932).

Costello R. B. (1984): Random House Webster’s College Dictionary. New York: Random House.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihály. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins.

de Botton, A., & Armstrong, J. (2013). Art as Therapy. London: Phaidon Press.

de Solla Price, D. J. (1986). Little science, big science… and beyond. New York: Columbia University Press.

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science, 16(12), 939-944.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). New York: Oxford University Press.

Gove, P. B. (1971). Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language: Unabridged. Springfield: G. and C. Merriam Company.

MacDonald, R., Kreutz, G., Mitchell, L. (2012). What is music, health, and wellbeing and why is it important? In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health and wellbeing (pp. 3-11). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McMahon, D. M. (2012). The pursuit of happiness in history. In I. Boniwell & S. Davis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 80-93). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Niemiec, R. M., & Wedding, D. (2008). Positive psychology at the movies: Using films to build virtues and character strengths. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe.

Niles, J. D. (1999). Homo narrans. The poetics and anthropology of oral literature. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Pargament, K. I. (2002). The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Psychological Inquiry, 13(3), 168-181.

Pawelski, J. O. (2012): Happiness and its Opposites. In I. Boniwell & S. Davis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 326-336). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pawelski, J. O., & Moores, D. J. (2012). The Eudaimonic Turn: Well-being in Literary Studies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Quiroga Murcia, C., Kreutz, G., Clift, S., & Bongard, S. (2010). Shall we dance? An exploration of the perceived benefits of dancing on well-being. Arts & Health, 2(2), 149-163.

Schneider, S. L. (2001). In search of realistic optimism: Meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. American Psychologist, 56(3), 250-263.

Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

Seligman, M. E., & Schulman, P. (1986). Explanatory style as a predictor of productivity and quitting among life insurance sales agents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(4), 832-838.

Sharp, C., Smith, J. V., & Cole, A. (2002). Cinematherapy: Metaphorically promoting therapeutic change. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 15(3), 269-276.

Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How to increase and sustain positive emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing best possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 73-82.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249-275.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271-324.

Tiberius, V. (2012). Philosophical Methods in Happiness Research. In I. Boniwell & S. Davis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 315-325). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tolstoy, L. (2010). The death of Ivan Ilych. New York: SoHo Books. (Original work published in 1886).

Västfjäll, D., Juslin, P. N, Hartig, T. (2012). Music, subjective wellbeing, and health: The role of everyday emotions. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health and wellbeing (pp. 405–423). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

* Please refer to Pargament (2002) for an overview of the connection of religious practices and well-being, to de Botton and Armstrong (2013) for a framework of how people use art to cultivate flourishing, to Niemiec and Wedding (2008) on the use of story-telling (especially movies) for building character strengths, and Pawelski and Moores (2012) for a treatise on the “eudaimonic turn” in literary studies.

Appendix

To himself

Be yet still undeterred! Accept yet still no loss! Bend to no bad luck’s blow, stand higher than ill will. Take joy, you, in yourself and think it is no woe. If all against you – luck, place and time – have sworn.

That which afflicts or cheers, hold all as predesigned. Take what your fate declares. Let there be no regret. Do what must now be done, ere one dispatches you. What you can hope for still, that will yet still be born.

Why wails, why lauds one still? One’s hardships and one’s luck, Is each one for himself. Examine every thing; This all is within you. Discard your fond illusion. And, ere you further step, go back into yourself. Who his own master is and keeps himself in check. He o’er the outspread world and all things there does reign.

(Paul Fleming)

Picture Source

Yesterday, I gave a one-hour introductory talk on Positive Psychology. Yet, the listeners weren´t your usual business crowd. The talk was embedded in a convention of about 100 undertakers (more formally: morticians); precisely, they were a youth organization (in this case meaning: under 40) of the “German Association of Morticians”. The convention was held in a larger hotel complex and there even was an exhibition for hearses, caskets, urns, and other…well…undertaker supplies. Actually, some of the regular hotel guests looked a bit scared.

Yesterday, I gave a one-hour introductory talk on Positive Psychology. Yet, the listeners weren´t your usual business crowd. The talk was embedded in a convention of about 100 undertakers (more formally: morticians); precisely, they were a youth organization (in this case meaning: under 40) of the “German Association of Morticians”. The convention was held in a larger hotel complex and there even was an exhibition for hearses, caskets, urns, and other…well…undertaker supplies. Actually, some of the regular hotel guests looked a bit scared.