Latest Blog Posts

Which Super-Power would You rather Possess: Fighting Evil or Promoting Good?

In order to learn more about the meaning of the word/concept “positive” in “Positive Psychology” (which the following post is all about), I highly encourage you to visit the website of James Pawelski, where he provides an in-depth analysis.

OK. So here´s a question for you: Some higher being has chosen to endow you with super-powers. You get to choose between two different profiles:

Let me elaborate a bit more on this:

- So, you could either be Mr. Red Cape. He´s your typical super-hero. He fights “the Bad”: Kicks the shit out of the bad guys, saves people from collapsing skyscrapers, and might even have the power to fight epidemics and end the occasional war. But: he cannot create “the Good”.

- Or, you could be Mr. Green Cape. He´s a different kind of super-hero. He has the ability to spread trust and love, and give meaning to individuals and whole communities etc. . But: he cannot eradicate “the Bad” – he definitely cannot end poverty and other calamities for good.

Mind you, this is an either-or story. You have 100% of one side – and 0% of the other. Who would you want to be – and why?

I won´t give you an answer here – because there is no single “right” solution.* But maybe, you´d like to think (or rather: feel) it through – and then share your thoughts in the comment section…?

*Although James Pawelski, MAPP´s academic director and Chief Philosophy Officer, is not too fond of simple and easy answers, he probably would have one for you here. But I´m not going to write it down – so as not to be the spoilsport for future Mappsters and listeners of his beautiful lectures in general…

Picture source: red cape, green cape

Does having a Child make us Happier or Unhappier? Or is that the wrong Question?

I´m pretty sure that all the parents among my readers will join into a roaring “HAPPIER!” when answering the first question in this post´s headline. Yet, it turns out that an unanimous scientific answer to that question is rather hard to find – as there´s a lot conflicting data out there.

There are papers that show well-being drops for both men and women when a first child comes into the house – and it typically does not rise that much until the children leave for college. Other researchers found that a first child markedly increases happiness, especially with the fathers, and the more so when it´s a boy. Then, there are papers that give the classic answer for lawyers (and psychologists as well): It depends. Or rather, there are upsides and downsides. E.g., mother are more stressed – but less depressed.

When there´s a lot conflicting research on a certain topic, it´s always a good thing to carry out a meta-analysis, which is a weighted integration of many studies on one area of inquiry. Such a meta-analysis has been done in 2004. Here´s the summary:

This meta-analysis finds that parents report lower marital satisfaction compared with nonparents (d=−.19, r=−.10). There is also a significant negative correlation between marital satisfaction and number of children (d=−.13, r=−.06). The difference in marital satisfaction is most pronounced among mothers of infants (38% of mothers of infants have high marital satisfaction, compared with 62% of childless women). For men, the effect remains similar across ages of children. The effect of parenthood on marital satisfaction is more negative among high socioeconomic groups, younger birth cohorts, and in more recent years. The data suggest that marital satisfaction decreases after the birth of a child due to role conflicts and restriction of freedom.

What they say is: On average, marital satisfaction drops slightly when a first child is born. The effect is stronger for women than for men, and the younger and richer the parents are. Parents struggle with stress due to role conflicts and a decrease in self-determination.

Are Children supposed to make us Happier?

But maybe, asking about satisfaction and happiness is not the right question after all. Is it really the “job” of our children to make us happier and more satisfied as a parent? I don´t think so. When a child comes into your life, you lose tons of money, you lose tons of sleep (and that´s due to dirty diapers, not dirty sex…), and you have to carry out planning and preparations on a regular basis that in their complexity can be likened to the Normandy landing – just for going to the movies on a Friday night.

But maybe, asking about satisfaction and happiness is not the right question after all. Is it really the “job” of our children to make us happier and more satisfied as a parent? I don´t think so. When a child comes into your life, you lose tons of money, you lose tons of sleep (and that´s due to dirty diapers, not dirty sex…), and you have to carry out planning and preparations on a regular basis that in their complexity can be likened to the Normandy landing – just for going to the movies on a Friday night.

Having children does not make us happy all the time. Period.

Yet, we get something else, research suggests: Purpose. Meaning. Unconditional love (especially when you have some sort of food, that is…). Asking for satisfaction is looking at the wrong axis of the Eudaimonia-Hedonia-Grid depicted above.

Being a parent is not a “fun” job at times – especially for the mothers (given a more traditional role-taking). Remember that viral video about the toughest job in the world?

But then: it definitely can be a blast. When researchers see a lot of conflicting data, they sometimes turn to what in science lingo is called “anecdotal evidence”. They tell a story. Here´s a story about my family having fun in the park (Photos taken by Tina Halfmann).

Enjoy!

Want to be Happy today? Check out the “Good Day Theory”…

A couple of minutes ago, I went out to go to my favorite café in order to work on a MAPP final paper. Now, I´m blogging. By the way, if you want to have some real good advice on following through with your plans, check out Peter Gollwitzer´s research on implementation intentions. But I digress…

So, when I went out of the door, I saw this sticker on a street light – basically, directly in front of our home. And I wonder how many times I might have passed it without noticing – but of course, it could be new as well.

Via Google, I´ve found out that it´s the name of a local rock band – I´ve posted one of their videos at the bottom of this post. The good news is: there really is a kind of “good day theory” in Positive Psychology. At least, there´s a paper by the name of What makes for a good day? Competence and autonomy in the day and in the person

What they found: a good day typically is characterized by frequent fulfillment of our needs for autonomy and competence. In plain English:

A good day in one where you decide what to do – and then choose to do something that you´re really good at.

So do that. Now…

Probably the most important message ever – but hard to grasp for some of us

So I found this yesterday on one of my friend´s Facebook page. I copied the pictured and forgot to write down who it was. Please notify me if you see this to get proper credit.

But anyway, the original source for this postcard is the artist and motivational speaker Liv Lane. I´ve never heard of her before (living in Germany might be a good excuse for that…) – but below, you can see one of the very fundamental truths about our nature as human beings. It took me about 30 years to reach that insight – and sadly, a lot of people never get to that point of intuitive wisdom.

But once you understand, everything is different…

Positive Psychology and MAPP at Penn: Doing that Namedropping Thing

Actually, I should be busy writing on my MAPP final papers right now. But then, taking short breaks is supposed to help your mind stay fresh, right?

By now, a lot of people that have read my blog also contacted me to ask about my MAPP experience. Obviously, it´s not that easy to tell a story of 10 months in a few sentences. Hey, that´s why I started this blog in the first place…* There´s also been some questions about the tuition – and to be honest, it´s not exactly a bargain. I could have not taken part without some generous support from my employer (or rather: my boss). But hey – Penn belongs to the Ivy League and that comes with a price tag.

If you´d like to know why I am convinced that it was worth each and every penny (and much more…), please read my blog front to back. Otherwise, you might be convinced by the sheer (work-)force of people that you’ll have the pleasure and honor to learn from. So here is the name-dropping list. Please note that the guest lecturers and assistant instructors will vary from year to year (C = core faculty; G = guest lecturer; A = assistant instructor that has taught part of a class at some point):

- Roy Baumeister, Professor of Psychology at Florida State University, author of Willpower and >500 other books and research articles (G)

- Paul Bloom, Professor of Psychology at Yale, author of Just Babies, his research has been published in “Nature” and “Science” (G)

- Dan Bowling, Senior Lecturing Fellow at Duke Law School, Visiting Scholar at Penn, and former SVP Human Resources at Coca-Cola (A)

- Lisa Buksbaum, CEO and Founder of NFP Soaringwords, former marketing executive (G)

- Art Carey, Columnist at the Philadelphia Inquirer, Pulitzer Prize winner for team coverage of the Three Mile Island disaster (G)

- Ellen Charry, Professor of Theology at Princeton Theological Seminary, author of (among other books) God and the Art of Happiness (G)

- Jer Clifton, Ph.D. student at the Positive Psychology Center, former manager at Habitat for Humanity (A)

- David Cooperrider, Professor or Organizational Behavior at Case Western Reserve University, “inventor” of Appreciative Inquiry (G)

- Jonathan Coopersmith, Chair of Musical Studies at the Curtis Institute of Music (G)

- Angela Duckworth, Professor of Psychology at University of Pennsylvania, “inventor” of Grit (C)

- Jane Dutton, Professor of Business Administration at University of Michigan, one of the world´s foremost authorities on Positive Organizational Scholarship (G)

- Johannes Eichstaedt, Ph.D. student at the PPC, first German MAPP alumnus (A)

- Chris Feudtner, Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania (G)

- Barbara Fredrickson, Professor of Psychology at University of North Carolina, “inventor” of the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (G)

- Jane Gillham, Professor of Psychology at Swarthmore College, co-author of The Optimistic Child (C)

- Adam Grant, Professor at Wharton Business School, author of Give and Take (G)

- Jonathan Haidt, Professor for Ethical Leadership at Stern School of Business, author of The Happiness Hypothesis (G)

- Rosie Hancock, Career Coach and Executive Consultant (A)

- Margaret “Peggy” Kern, Postdoctoral Fellow at Penn, Stats Wizard and my capstone project supervisor (C)

- Emilia Lahti, “Queen of Sisu” (and overall awesomeness) (G)

- Ellen Langer, Professor of Psychology at Harvard, one of the world´s foremost experts on mindfulness (among other things) (G)

- Dan Lerner, Instructor at New York University and Personal Coach (A)

- Mark Linkins, (among other things) Lead Consultant for Educational Practices at the VIA Institute on Character (G)

- Meredith Myers, Full-time Lecturer at Wharton and Ph.D. student at Case Western Reserve University (C)

- Ryan Niemiec, Education Director of VIA Institute on Character, author of Positive Psychology at the Movies (G)

- James O’Shaughnessy, Managing Director of Floreat Education, former Director of Policy and Research for Prime Minister D. Cameron (G)

- Ken Pargament, Professor of Psychology at Bowling Green University, author of Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy (G)

- James Pawelski, Director of Education at the Positive Psychology, MAPP´s “Master of Ceremony” (C)

- Isaac Prilleltensky, Dean of the University of Miami School of Education (G)

- John Ratey, Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, author of Spark (G)

- Tom Rath, Senior Scientist and Advisor to Gallup, author of (among other books) How full is your Bucket? (G)

- Amy Walker Rebele, Positive Psychology Educator (A)

- Robert “Reb” Rebele, Positive Psychology Educator and Consultant (A)

- Karen Reivich, Co-Director of the Penn Resiliency Project, author of The Resilience Factor (C)

- Ann Roepke, Ph.D. student at Penn´s Positive Psychology Center (G)

- Paul Rozin, Professor of Psychology at Penn, one of the leading experts on the psychology of food (G)

- Esa Saarinen, Professor of Applied Philosophy at Aalto University one of Finland´s foremost philosophers (G)

- Judith Saltzberg-Levick, Instructor at Penn, Psychologist specialized in CBT (C)

- Barry Schwartz, Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at Swarthmore College, author of The Paradox of Choice (G)

- Charles Scudamore, Vice Principal at Geelong Grammar School, Australia (G)

- Martin Seligman, Professor of Psychology at Penn, “Spiritus Rector” of Positive Psychology (C)

- Andrew Soren, Leadership Coach and Consultant (A)

- Karen Warner, CEO at executive coaching firm “Tangible Group” (A)

- Chandra Sripada, Professor of Psychiatry at University of Michigan (G)

- Daniel Tomasulo, Psychologist, Author, Columnist, author of Confessions of a Former Child (A)

- George Vaillant, Professor at Harvard Medical School, former Director of the Harvard Grant Study (G)

- Lea Waters, Professor of Psychology at University of Melbourne (G)

- Amy Wrzesniewski, Professor of Organizational Behavior at Yale, one of the leading experts on job callings and meaningful work (G)

- David Yaden, Ph.D. student with Martin Seligman (A)

That´s value for money…

*And to become super-duper famous, of course…

The World is Changing and I´m on the Transition Team

I just had to share this. Found it on the Facebook page of Louis Alloro who was in MAPP a couple of years before me…

Mappsterview No. 4: Dan Bowling on Turning the Tide at Coca-Cola and Lawyer (Un-)Happiness

I was in the ninth cohort of the Master of Applied Positive Program at Penn. Consequently, there are tons of brilliant MAPP Alumni out there that have very fascinating stories to tell: about their experience with the program, about Positive Psychology in general – and about themselves of course. I really want to hear those stories. That´s why I started to do Mappsterviews* with my predecessors.

Today, you are going to meet Dan Bowling, very successful lawyer turned very successful manager turned very successful Law and Positive Psychology teacher and researcher. Actually, I´m supposed to be writing MAPP finals instead of blogging right in this moment. Such is life. Our final papers are a lot about going through our former papers and teaching notes, about integrating and “hunting the good stuff”. Yesterday, I wrote a passage about my “heureka moments” in MAPP. And since I like to link my insights to the people that are “responsible” for those insights, here´s what I wrote about Dan Bowling:

If something is worth doing, it’s worth doing it with style.

Please introduce yourself briefly:

My name is Dan Bowling. I am Senior Lecturing Fellow at Duke Law School, where I teach courses on labor law, employment law, and positive psychology and the practice of law. These classes seem to be popular among the students, maybe because I bring pizza and wine for the class every now and then. I also run a small consultancy, Positive Workplace Solutions LLC, which provides executive coaching and legal consulting for C-Level executives and professionals (I am a licensed attorney). I work with Martin Seligman’s team at UPenn’s Positive Psychology Center doing empirical research on strengths and lawyers, and have helped teach in MAPP for the past 5 years. I speak regularly at legal and/or positive psychology conferences, and write a featured blog for Talent Management Magazine called Psychology at Work. I tweet silly and irrelevant stuff @BowlingDan if you would like to follow me.

My name is Dan Bowling. I am Senior Lecturing Fellow at Duke Law School, where I teach courses on labor law, employment law, and positive psychology and the practice of law. These classes seem to be popular among the students, maybe because I bring pizza and wine for the class every now and then. I also run a small consultancy, Positive Workplace Solutions LLC, which provides executive coaching and legal consulting for C-Level executives and professionals (I am a licensed attorney). I work with Martin Seligman’s team at UPenn’s Positive Psychology Center doing empirical research on strengths and lawyers, and have helped teach in MAPP for the past 5 years. I speak regularly at legal and/or positive psychology conferences, and write a featured blog for Talent Management Magazine called Psychology at Work. I tweet silly and irrelevant stuff @BowlingDan if you would like to follow me.

What got you interested in Positive Psychology in the first place?

I have always been fascinated by different personality traits. I started my career after graduating from Duke Law in 1980 as a labor and employment litigator and it struck me how important a role personality played in why one employee sues you and another doesn’t, even if their job circumstances are the same. I made partner in a large Atlanta law firm in 1986 but was shortly thereafter recruited by Coca-Cola to help form the new law department of its bottling operations, which it spun off as Coca-Cola Enterprises in the largest IPO in history. My interests in the psychological components of work continued during my career with Coca-Cola Enterprises, where I held a variety of jobs including President of a nine-state, 2 billion dollar operating region, as I developed a firm belief in the link between optimism and positive emotions in employee and corporate performance.

I had the opportunity to put my theories into practice in the latter stages of my career, when I was named head of human resources for the entire company. Frankly, the organization was down. We were under legal assault by small groups of hostile employees. Rather than aggressively defending the claims – which I found spurious – our programs and energies were focused on an agonized self-examination of what we did to prompt such claims. The halls were full of consultants and lawyers and days were consumed by meetings, all focused on what was “wrong” with us and how we could treat it. Not surprisingly, our “disease” was metastasizing, and corporate maladies previously unknown (or non-existent) were being discovered and stern remedies subscribed. Managers and employees forgot about selling Coke and spent their time instead in a variety of “workshops,” the corporate equivalent of Mao’s re-education camps.

Our new HR team decided to flip the paradigm, and look at what was right about the company – a focus on the life above zero, as Marty Seligman says. It didn’t take long to learn that the vast majority of the employee grievances were brought by a handful of perpetually complaining employees, often sponsored by outside interest groups, and were generally unfounded. We also found that most of our employees were quite happy with us as an employer. We starting asking a very basic question of ourselves: “Why is it 95% of our HR programs and initiatives are focused on the 5% of employees who hate us? Why spend our precious resources and energies on the perpetually dissatisfied few? Why not focus on efforts on those who want to build a better company and believe we can?” Eventually, we resolved our issues quite successfully, the grumblers moved on, and we spent the rest of our time in HR doing things to hire and engage people who were a positive contribution to our company. When I turned 50, it was time to move on, so I joined the Duke Law faculty teaching labor and employment law, while continuing my research into optimism and positive personality traits by receiving a masters in applied positive psychology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Your are a lawyer, you teach law, and via MAPP (at the lastest…) you know that lawyers are among the unhappiest professions. Why do you think that is the case?

That question is at the core of my current research and writing interests. First, I must challenge the premise – I think the data is not conclusive that lawyers are among the unhappiest professions, although the majority of the literature seems to suggest so. Regardless, law school and law practice seem to exacerbate depressive tendencies in persons with those tendencies, which isn’t surprising given the number of hours lawyers work in pressurized environments on things they are not intrinsically motivated to do. But as to whether lawyers as a population are significantly unhappier than other large groups of highly educated professionals, more research is needed.

Do you have plans to do anything about that?

To effect real change in the profession, it is of critical importance to establish a link between well-being and legal professionalism for the happiness of lawyers to be taken seriously, and my goal is to help provide that framework for the legal profession.

According to what you´ve learned about Positive Psychology, if I were the CEO of a company: what are three things that I should start doing right away?

1) Identify and develop leaders who are optimistic and enthusiastic about the success of others; 2) incorporate strengths-based employee assessment and development programs; and 3) use better psychometrics to support the hiring and talent acquisition process.

Thank you, Dan, for this Mappsterview! If you are a MAPP alumnus and would like to have your story featured here – please go ahead and shoot me an e-mail!

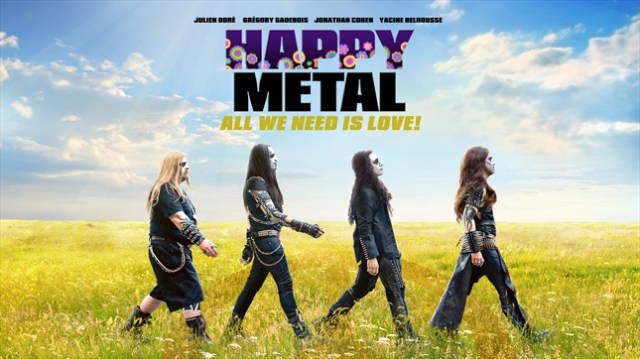

On Music and Well-Being – or: The Garden of our Lord is Vast and Plentiful…

MAPP is a fulltime program – but combines onsite classes with long-distance learning periods. Part of the distance learning comprises a lot of reading (…who would have thought of that…) and writing essays about a wide array of positive psychology topics. I´ve decided to post some of those essays here on Mappalicious. Surely, they´re not the be-all and end-all of academic writing. But then again, it would also be a pity to bury them in the depths of my laptop…

The sentence displayed in the title is a well-known proverb in Germany. I could not find a passage with that exact meaning directly in the Bible. Therefore, it seems to be more of a piece of folk wisdom. Mostly, one is inclined to use it situations where one is subjected to, by way of example, a piece (or genre) of music that one does not like – but that is highly appreciated by other people. It is a way of acknowledging that people have different tastes in just about anything – and that one “is fine” with that.*

In that sense, it has some shared meaning with the English figure of speech “different strokes for different folks”. While I am writing these sentences, there´s a portrait of Michael Wendler on TV, a leading protagonist of German “Schlagermusik”, a particularly corny, banal, uniform, and (to my ears) horrible style of pop music that sells really well and is played at most parties at some point or the other. For the most part of my life, I have enjoyed music that is often considered to be at the opposite end of the musical spectrum: heavy metal. In this essay, I would like to muse about this phenomenon: Why are people drawn to different kinds of music (and art in general) – and what does this phenomenon have to say about human well-being?

The question of how to lead a good life is a very old one. Religious leaders, philosophers, authors and laymen alike have tried to find answers to this mystery. At earlier stages of this quest, it was mostly put into question that feeling happy and experiencing positive emotions is an essential part of a life well-lived. Yet, with the appearance of the Enlightenment (at the latest), the pursuit of happiness can be seen as a central element of this overall endeavor (McMahon, 2008). Nowadays, there is convincing scientific evidence for the link between positive emotions and (psychological) well-being (Fredrickson, 2001).

For at least as long as people have pondered on the meaning of human life – and the question if (and how) the pursuit of happiness can play a role in finding the right answers – they have immersed themselves in art. Primitive forms of musical instruments, paintings, and pieces of stoneware have appeared at least 30,000 years before our time. Nowadays, due to its easy and ubiquitous availability, music may be the most widespread form of art (at least it seems to be most widely used). In a study using experiencing sampling, a method where subjects are to record what they do in their lives at certain intervals, it was found that music was present in 37% percent of the samples; and that this music influenced the emotional state of the listeners in 67% of these events (Juslin, Liljeström, Västfjäll, Barradas, & Silva, 2008).

The last-mentioned number hints to a possible explanation for the immense pervasiveness of music: it is a potent means for regulating affect. Listening to music can lift our mood, alleviate psychological stress as well as physical pain, and contribute to our overall well-being (Västfjäll, Juslin, & Hartig, 2012). This may be a consequence of the uplifting effect of listening to music, but could also be a byproduct of its social aspect, since it is often performed and listened to in the presence of other human beings (MacDonald, Kreutz, & Mitchell, 2012). Additionally, making and listening to music is able to induce flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996). For all these reasons, it is also used in a wide array of psychotherapeutic settings (Västfjäll, Juslin, & Hartig, 2012).

The introductory paragraph of this essay alludes to the fact that different people like to listen to different styles of music. Therefore, what brings pleasure, uplift, and well-being to one person may result in anger and unpleasantness for another. This may be a consequence of learning and a kind of “cultural conditioning”, but could also be explained by more basic psychological (even psycho-physiological) phenomena. Västfjäll, Juslin, & Hartig (2012) list several aspects that could account for music´s propensity to be a medium of mood control. Among them are

- brain stem reflexes (e.g., reactions to loudness and speed);

- rhythmic entrainment (reactions to the recurring metrical quality);

- and visual imagery evoked by a piece of music.

Since different people obviously have different nervous systems (e.g., in terms of responsivity and sensibility) it seems self-evident that they should react more or less favorably to varying styles of music. Maybe, it is not even a choice that we make consciously.

Can we really choose what style(s) of music we are attracted to?

One of my favorite movies of all time is Gerry Marshall´s “Pretty Woman” (1990). There is a scene where the male main protagonist, successful businessman Edward Lewis (played by Richard Gere), invites the female mail protagonist, prostitute Vivian Ward (played by Julia Roberts), to the San Francisco Opera to see a premier of “La Traviata”. When Vivian is very moved by the music, Edward says:

People’s reactions to opera the first time they see it is very dramatic; they either love it or they hate it. If they love it, they will always love it. If they don’t, they may learn to appreciate it, but it will never become part of their soul.

From my own experience, I feel that I know very well what Edward is talking about. Only, in my case, it wasn´t opera but heavy metal. I was exposed to this style of music for the first time at age 14, specifically a song by the German metal band Helloween. They are considered to have established their own sub-genre in 1985 which can be characterized by the following attributes:

- exceptionally high tempo;

- frequent use of double-bass drum technique;

- frequent use of double (harmonic) lead guitars;

- distinctly high-pitched male singers;

- lyrics that are oftentimes based fantasy and sci-fi topoi.

I remember my parents saying that heavy metal would be a “phase” I was going through – but so far, time has proved them wrong. I still love it and probably will do so until the end of this life. Of course I do listen to other music. I went to an opera premier of “Don Giovanni” in March of 2013, and I also enjoyed listening to Tschaikowski and other Russian composers when we went to an evening at the Philadelphia Philharmonic Orchestra as part of the MAPP program in January 2014 – but honestly speaking, classical music will (most likely) never captured my heart the way that heavy metal has done. I know that one can learn to appreciate classical music in the same way that one has to learn how to appreciate good wine – but to me, that´s not the same as “falling in love” with a particular style of music.

There is not much official (psychological) research on heavy metal. Yet, because of the above-mentioned attributes, it is oftentimes described as the most aggressive style of music. Following that notion, most of the few studies that do exist typically deal with supposed negative consequences (or correlates) of listening to heavy metal, such as aggressive behavior, suicidal risk, drug abuse, and low self-esteem (e.g., King, 1998; Arnett, 1992; Scheel & Westefeld, 1999). I am trying hard not to be lopsided here – but to me there seems to be something wrong about these studies. Heavy metal is – for the most part – aggressive music, agreed. But this does not automatically imply heavy metal fans are aggressive people. I have been to hundreds of concerts in my lifetime. From these experiences, I can say that heavy metal concerts are distinctly peaceful and non-violent places. My observation is echoed by one of those rarer studies that finds metal fans are just regular people that happen to feel good while listening to high-intensity music (Gowensmith & Bloom, 1997). The study concludes by stating that the

[…] most widely accepted conclusion is that heavy metal fans are in general angrier, more agitated, and more aroused than fans of other musical styles. The results of this study do not support this speculation. No […] differences were found among subjects’ levels of state arousal, state anger, or trait anger. (p. 41)

Instead, the researchers were able to detect an interaction effect. In fact, there were people in their sample that got overly aroused and even aggressive when listening to heavy metal: precisely, persons that stated they do not like heavy metal (especially fans of country music). For fans of metal music, listening to their favorite music did not result in elevated levels of arousal or negative emotion – quite the contrary. This finding is mirrored in an article on the internet site of the magazine “The Atlantic” by the name of Finding Happiness in Angry Music (Sottile, 2013). The author concludes that potentially there is “something cleansing about engaging with emotions we might not usually let ourselves feel”. Hence, music does not necessarily have to be happy in order to make us happy – and foster our well-being. It all comes down to “different strokes for different folks” again. In their review article on the connection of music and well-being, Västfjäll, Juslin, and Hartig (2012) draw a similar conclusion when making the point that music as a stimulus cannot be the same for all listeners:

Thus, there are no “pure” effects of music that will invariably occur regardless of the specific listener or situation. The response will depend on factors such as the listener´s music preferences and previous experiences, as well as on the specific circumstances of the context. (p. 408)

As a consequence, I feel we should be careful to make (too) strong judgments about other people´s taste in music (and art in general). Ever so often, many ways lead to Rome. I oppose to the distinction that is often made between “serious music” (sometimes called “art music”) and the more “popular” styles of music that also comprise heavy metal. The aspect of seriousness is inherent in the listener, not the music itself. One can listen to Mozart carelessly – while savoring heavy metal and thereby displaying a great amount of mindfulness.

The garden of the Lord is vast and plentiful. In order to find happiness, I believe, we must find our personal parcel of land in that garden – and then start to cultivate it.

References

Arnett, J. (1992). The Soundtrack of Recklessness Musical Preferences and Reckless Behavior among Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(3), 313-331.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihály (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York: Harper Collins.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226.

Gowensmith, W. N., & Bloom, L. J. (1997). The effects of heavy metal music on arousal and anger. Journal of Music Therapy, 34, 33-45.

Juslin, P. N., Liljeström, S., Västfjäll, D., Barradas, G., & Silva, A. (2008). An experience sampling study of emotional reactions to music: listener, music, and situation. Emotion, 8(5), 668-683.

King, P. (1988). Heavy metal music and drug abuse in adolescents. Postgraduate Medicine, 83(5), 295-301.

MacDonald, R., Kreutz, G., Mitchell, L. (2012). What is music, health, and wellbeing and why is it important? In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health and wellbeing (pp. 3-11). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marshall, G. (1990): Pretty Woman [Film]. Los Angeles, Touchstone Pictures.

McMahon, D. M. (2008). The pursuit of happiness in history. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 80-93). New York: Guilford Press.

Scheel, K. R., & Westefeld, J. S. (1999). Heavy metal music and adolescent suicidality: An empirical investigation. Adolescence, 34, 253–273.

Sottile, Leah (2013). Finding happiness in angry music.

Västfjäll, D., Juslin, P. N, Hartig, T. (2012). Music, subjective wellbeing, and health: The role of everyday emotions. In R. MacDonald, G. Kreutz, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Music, health and wellbeing (pp. 405–423). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

* Mostly though, the phrase will be accompanied by an incredulous shake of the head, thereby signifying that, at the end of the day, one´s own taste is to be valued higher.

Short Film: The Importance of Kindness

Strings a chord with me…