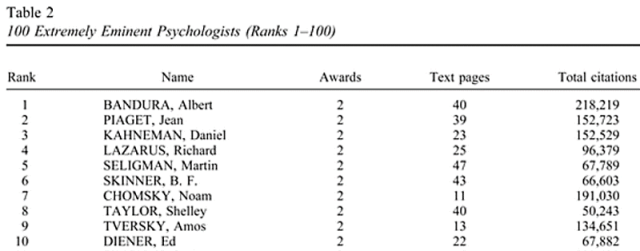

Ever since graduating from the Penn MAPP program, I give a handful of presentations and keynotes on Positive Psychology each quarter. Since I´m an executive in a multinational corporation, I mostly get invited to talk to fellow businessmen, and the greater part of my talks addresses human resources, leadership, and organization culture topics. One of the charts I show early on in each and every presentation is this one:

I deliberately show it early in the game in order to convey that Positive Psychology is not a sort of Happyology, that it´s not about wearing rose-colored glasses all the time. Yet, it also serves to clarify the consequences of different human resources and leadership behaviors and programs. One of the most important takeaways:

Hedonic and eudaimonic pathways both play a crucial role in order to keep employees fully engaged and productive – but most measures that foster hedonic experiences are rather short-lived and, perhaps even more important, easy to copy by competitors – whereas conditions that foster meaning an purpose are rather hard to replicate.

Yesterday, I stumbled upon an exquisite book chapter by University of Ottawa researcher Veronika Huta which explains in detail the differences between hedonic and eudaimonic orientations in life (and work). She analyzed a multitude of definitions and conceptions on the differences of hedonia and eudaimonia from previous research and boiled them down to a comprehensible set of attributes. These are the most important takeaways.

Hedonia, in short, is about:

- pleasure, enjoyment, and satisfaction;

- and the absence of distress.

Eudaimonia is more complex in it´s nature, it´s about:

- authenticity: clarifying one’s true self and deep values, staying connected with them, and acting in accord with them;

- meaning: understanding a bigger picture, relating to it, and contributing to it. This may include broader aspects of one´s life or identity, a purpose, the long term, the community, society, even the entire ecosystem;

- excellence: striving for higher quality and higher standards in one’s behavior, performance, accomplishments, and ethics;

- personal growth: self-actualization, fulfilling one’s potential and pursuing personal goals; growth, seeking challenges; and maturing as a human being.

Other important attributes and distinctions:

Hedonia is associated with:

- physical and emotional needs;

- desire;

- what feels good;

- taking, for me, now;

- ease;

- rights;

- pleasure;

- self-nourishing and self-care; taking care of one’s own needs and desires, typically in the present or near future; reaching personal release and peace, replenishment; energy and joy.

Eudaimonia is associated with:

- cognitive values and ideals

- care;

- what feels right;

- giving, building, something broader, the long-term;

- effort;

- responsibilities;

- elevation;

- cultivating; giving of oneself, investing in a larger aspect of the self, a long-term project, or the surrounding word; quality, rightness, context, the welfare of others.

To close, it is important to say that both pathways to happiness are not mutually exclusive (in the strict sense). Meaningful experiences can certainly bring about pleasure – and taking care of ourselves can certainly add meaning to our lives. As such, we must also refrain from equating the pursuit of hedonia with shallowness. As the graphic at the top of the article illustrates, we need to grow on both dimensions in order to live a truly fulfilling life.

Share and enjoy!

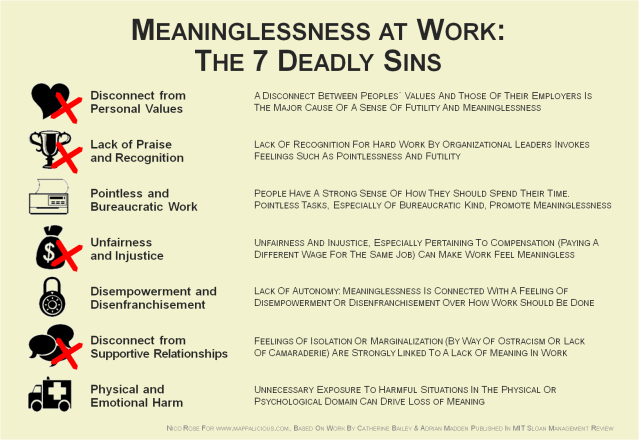

The final graphic is not my creation – the picture is taken directly from the article listed in the respective headline.

The final graphic is not my creation – the picture is taken directly from the article listed in the respective headline.

Most of us know these days: You´re rushing from one meeting to another, squeezing in those important calls with the tax consultant and your child´s class teacher – while desperately trying to finish that presentation for your boss which is due at 06:00 pm. This is what days at the office look like for a lot of who earn their money as so-called knowledge workers.

Most of us know these days: You´re rushing from one meeting to another, squeezing in those important calls with the tax consultant and your child´s class teacher – while desperately trying to finish that presentation for your boss which is due at 06:00 pm. This is what days at the office look like for a lot of who earn their money as so-called knowledge workers.

Today, I´d like to introduce two other approaches that aim at assessing organizational energy. In both, St. Gallen-based (Switzerland) Prof. Heike Bruch plays a major role.

Today, I´d like to introduce two other approaches that aim at assessing organizational energy. In both, St. Gallen-based (Switzerland) Prof. Heike Bruch plays a major role. Two of my academic heroes have published pieces in the New York Times recently.

Two of my academic heroes have published pieces in the New York Times recently.